When Americans celebrate the Fourth of July, we imagine fireworks, flags and a dramatic reading of the Declaration of Independence. We think we know the story: The Continental Congress selected Thomas Jefferson to write the declaration. He labored alone to produce this famous document. Congress then approved it unanimously and it was signed on July 4, 1776.

But the truth is far different and more complex. The story behind this iconic document ŌĆö the how, who, and why of its creation ŌĆö is just as explosive and illuminating as the day it represents. Far from a spontaneous outburst of rebellion, the Declaration was the product of political strategy, collaborative writing and a shared sense of urgency among men who knew their words would change the course of history.

By the spring of 1776, the American colonies were deep in conflict with Great Britain. Battles at Lexington and Concord had already been fought. George Washington was attempting to transform the continental army into a professional fighting force. Thomas PaineŌĆÖs "Common Sense" had ignited widespread public support for full separation from the British Crown. The Continental Congress had been meeting in Philadelphia, debating how far they were willing to go. By June, the mood had shifted from reconciliation to revolution.

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a resolution to the Continental Congress declaring ŌĆ£that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States.ŌĆØ The motion was controversial. Some delegates wanted more time to consult their colonies. But most in Congress knew that if independence was going to happen, it needed to be explained and justified to the world. So they created a committee to draft a formal declaration.

On June 11, 1776, the Continental Congress appointed a ŌĆ£Committee of FiveŌĆØ to write the declaration. The members were:

- John Adams of Massachusetts

- Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania

- Thomas Jefferson of Virginia

- Roger Sherman of Connecticut

- Robert R. Livingston of New York

This was not a random selection. Each man represented a different region of the colonies and had earned the trust of fellow delegates. Jefferson was relatively young but already known for his eloquence. Adams was an outspoken advocate of independence. Franklin brought wisdom, wit, diplomatic experience and international prestige. Sherman brought New England theological perspectives and legislative experience, while Livingston represented the more moderate New York delegation and brought keen legal insight.

Although it was a group project on paper, the heavy lifting fell to Thomas Jefferson. The committee chose him to draft the initial version. Why Jefferson? According to John Adams, Jefferson was chosen for three reasons: he was from Virginia (the most influential colony), he was popular, and, Adams admitted, ŌĆ£you can write ten times better than I can.ŌĆØ

The Declaration's editing process

Jefferson wrote the draft in a rented room at 700 Market Street in Philadelphia. He leaned heavily on Enlightenment ideas, especially those of John Locke, emphasizing natural rights and the notion that government derives its power from the consent of the governed. He also borrowed phrasing from earlier colonial declarations, including his own "A Summary View of the Rights of British America" and borrowed extensively from George MasonŌĆÖs "Virginia Declaration of Rights."

After Jefferson completed the initial draft (likely by June 28), he shared it with Adams and Franklin. Both men suggested revisions. Franklin, ever the editor, softened some of JeffersonŌĆÖs sharpest attacks and corrected language for flow and diplomacy. His most famous contribution was changing Jefferson's phrase "We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable" to the more secular and philosophically precise "We hold these truths to be self-evident."

Adams contributed to structural suggestions and to tone. He also contributed to the strategic presentation of grievances against King George III, understanding that the declaration needed to justify revolution in terms that would be acceptable to both colonial readers and potential European allies.

Sherman and Livingston played more limited but still meaningful roles. Sherman, with his theological background, helped ensure the document's religious references would appeal to Puritan New England, while Livingston's legal expertise helped refine the constitutional arguments against British rule. Otherwise, their involvement in the actual content of the declaration was likely minimal.

Debate and revision by the Continental Congress

The revised draft was presented to the full Continental Congress on June 28, 1776. What followed was a few days of intense debate and revision by the entire body.

From July 1 to July 4, the Continental Congress debated the resolution for independence and edited the Declaration. Jefferson watched as more than two dozen changes were made to his prose. The Congress cut about a quarter of the original text, including a lengthy passage condemning King George III for perpetuating the transatlantic slave trade that would have sparked deep division among the delegates, especially those from Southern colonies.

Other modifications included strengthening the religious language, toning down some of the more inflammatory rhetoric and making the grievances more specific and legally grounded. Congress made 86 edits, removing about a quarter of JeffersonŌĆÖs original content. Jefferson was reportedly frustrated by the changes, calling them ŌĆ£mutilations,ŌĆØ but he recognized that compromise was the cost of consensus

Despite the extensive revisions, the core of Jefferson's vision remained intact and on July 2, 1776, the Continental Congress voted in favor of LeeŌĆÖs resolution for independence. ThatŌĆÖs the actual date the colonies officially broke from Britain. John Adams even predicted in a letter to his wife that July 2 would be celebrated forever as AmericaŌĆÖs Independence Day. He was close. The official adoption of the Declaration came two days later.

Independence Day

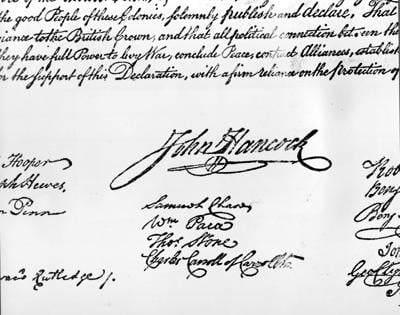

On July 4, 1776, Congress formally approved the final version of the Declaration of Independence. Contrary to popular belief, most of the signers did not sign it on that day. Only John Hancock, as president of Congress, and Charles Thomson, as secretary, signed then. The famous handwritten version, now in the National Archives, wasnŌĆÖt signed until Aug. 2. But the document approved on July 4 was immediately printed by John Dunlap, the official printer to Congress.

These first copies, known as Dunlap Broadsides, were distributed throughout the colonies and sent to military leaders, state assemblies and even King George III. George Washington had it read aloud to the Continental Army. This rapid dissemination was crucial to its impact, as it was needed to rally public support for the revolutionary cause and explain the colonies' actions to the world.

The Declaration wasnŌĆÖt just a break-up letter to the British Crown ŌĆö it was a manifesto for a new kind of political order. Its assertion that ŌĆ£all men are created equalŌĆØ would echo through centuries of American history, invoked by abolitionists, suffragists, civil rights leaders and more.

The creation of the Declaration of Independence demonstrates that even the most iconic documents in American history emerged from collaborative processes involving compromise, revision, and collective wisdom. While Jefferson deserves primary credit for the document's eloquent expression of revolutionary ideals, the contributions of his committee colleagues and the broader Continental Congress were essential to creating a text that could unite thirteen diverse colonies in common cause.

This collaborative origin reflects the democratic principles the declaration itself proclaimed, showing that American independence was achieved not through the vision of a single individual, but through the collective efforts of representatives working together to articulate their shared commitment to liberty, equality, and self-governance. The process that created the Declaration of Independence thus embodied the very democratic ideals it proclaimed to the world.

Today, the Declaration of Independence is enshrined as one of the foundational texts of American democracy. But itŌĆÖs worth remembering that it was created under immense pressure, forged by committee and edited by compromise. Its authors knew they were taking a dangerous step. As Franklin quipped at the signing, ŌĆ£We must all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately.ŌĆØ